Microwave ferrites: can they be made DIY? No. But I learned I was asking the wrong question.

2019-11-07-1 #1

Most of the cost of a magnetron reflection amplifier is in the circulator. High power circulators are weird and expensive but you can't build a reflection amplifier without them. Even just ordering special microwave ferrite material is almost as expensive as the finished circulator (if they'll sell to you at all). So naturally I wondered if I could make a ferrite disk, and from it a circulator, cheaply at home. Nickle ferrites are the most applicable because they can be worked in air. The two feasible options seem to be water chemistry nanoparticles, pressing, then sintering or low temp curing pourable magnetic composites made of expensive monomers, permalloy powder, and powdered oriented-strand 3M magnetic sheet.

But in the process I learned there's nothing special about garnet or other microwave ferrites. They just have a small resonance line width leading to low loss. The same non-reciprocal ferrimagnetic resonance happens even mass produced cheap iron ferrite rods and might work for an extremely lossy demo. Or at at high power but low duty cycle when you don't care about energy efficiency...like if you had a injection locked magnetron and bursty power to spare.

tldr: Home manufacture of microwave ferrites might be cheaply feasible *but* reuse of common cheap ferrites as lossy circulator elements certainly is and it's immediately accessible.

Circulator theory

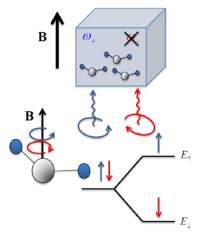

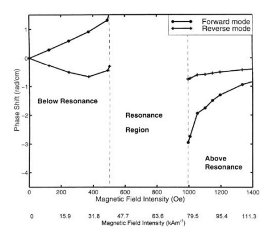

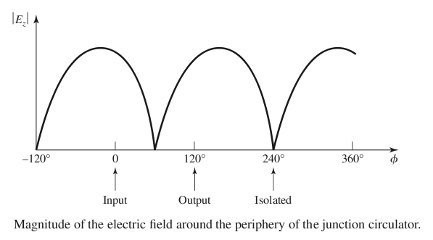

A circulator uses some non-reciprocal material that allow transmissions lines to work differently depending on which direction the RF is traveling. In electromagnetics non-reciprocity is almost exclusively obtained through Zeeman splitting in (ferrite) ferromagnetic materials using a static magnetic bias that splits degenerate atomic states with opposite spin. These opposite spins have slightly different energy and so different frequency. In the plot on the right below this frequency difference is represent as advance or retreat of phase.

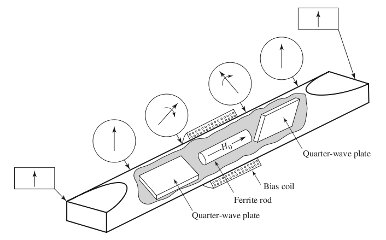

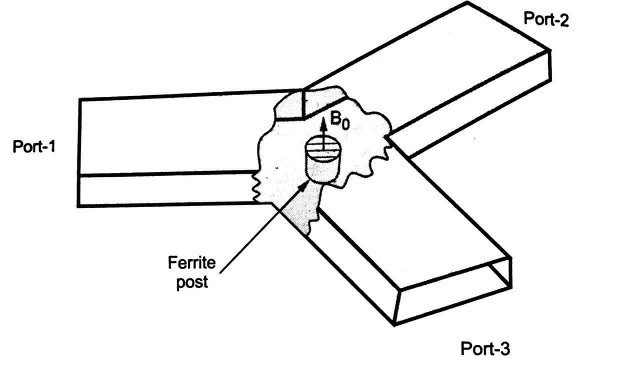

For circulators made of ferrites there are two ways main ways to use this. 1, magic-tee waveguides connected by two paths where one path is loaded with ferrite that causes faraday rotation of polarization (equiv to 180 deg phase shift) causing two-path interference in one direction but not the other (youtube link).

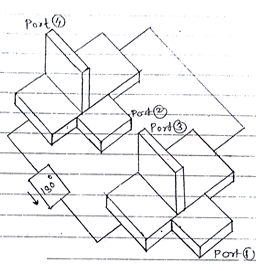

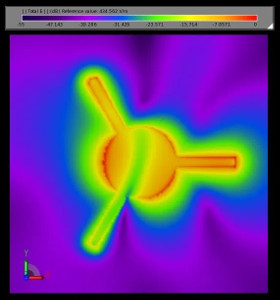

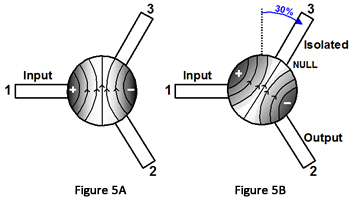

And 2, Y-junction transmission lines with ferrite resonators disks that have standing waves with nulls that can be rotated by an external magnetic field to so that the voltages at different angles around the perimeter of the resonator can be maximized and minimized.

The standing wave is actually two counter-rotating wave patterns. When there's no external magnetic field they rotate at the same frequency. When an external magnetic field is introduced the frequency of one is shifted and the resulting interference pattern is rotated. Despite the complexity of the physics in terms of mechanical construction a round ferrite waveguide based Y-junction circulator is by far the easiest design to make. And it's the easiest with which to connect a low power magnetron. The most straightfoward approach is the traditional 80*40mm TE_01 waveguide dimensions for the three arms.

Ferrite chemistry and mechanical production

The actual ferrimagnetic resonance is a frequency where the circulators *don't* work and they have to be designed with the target frequency either above the resonance in frequency or below it. Above or below resonance operation, depending on if the precession frequency is higher or lower than the RF frequency. The size of the the resonance in frequency span is called the line width and it determines the loss of the material. Expensive, densely pressed garnet ferrites have very low line widths and work over a broader range at lower loss.

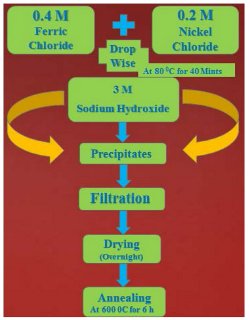

But this doesn't neccessarily mean that homemade nickel ferrite would have no use in a circulator. It'd only be lossy. So what I'm thinking about here is using simple water based chemistry with ferrite chloride and nickel chloride chelated to co-precipitate a nickle ferrite and attempt to manufacture the a homemade waveguide y-junction circulator.

Nickel Ferrites may be the least complicated ferrite from the processing point of view. The nickel remains essentially in the Ni++ state so that air is almost always used as the firing atmosphere.

For co-precipitated "ready" powders, like the above example, sintering temperatures can be as low as 900 C. That's plausible to do with a cheap induction heater like I have. The press could probably be a simple hydraulic press. Papers quote pressures around 100 MPa, so for a 3cm diameter disk and a 2 metric ton press thats: (2 tonne)⋅(9.8m/s^2)⋅10/(pi⋅1.5cm^2) = ~200 MPa. Plenty of margin. A $20 hydraulic bottle jack for trucks does about 6 ton. Though I imagine the limiting factor would be the threaded rod and nuts used to make the press frame. But it'd probably still have voids without proper compaction machines and the effective line width would be higher. So much higher that an improperly home-pressed nickle ferrite would probably be no less lossy than an industrial pressed iron ferrite availably commonly for cheap prices.

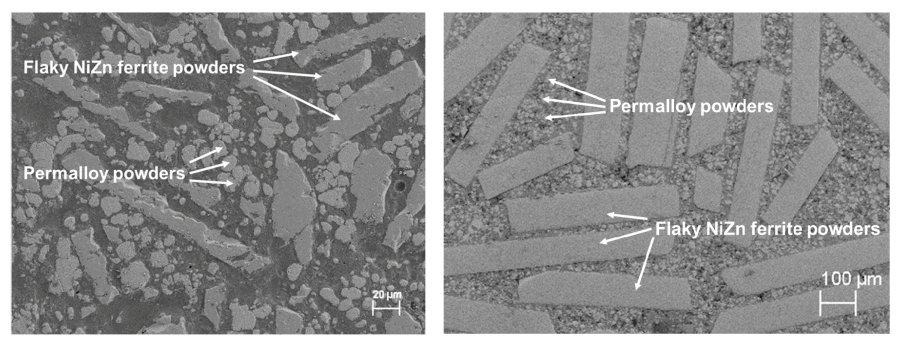

Pourable ferrite composites with no press and low temperature curing

But even a cheap press is an expense and a somewhat bulky and dangerous thing. And sintering at 900 C is hard in implementation. There are some papers about pourable low-temperature cured pourable magnetic composites. But most of these have terrible specs. Except one 2019 paper, A (Permalloy + NiZn Ferrite) Moldable Magnetic Composite for Heterogeneous Integration of Power Electronics that has both decent performance *and* it's easily manufactured DIY. It's a mix of expensive (but feasible) permalloy magnetic powder with NiZn ferrite from crushed up 3M Flux Field Directional sheet and expensive and infeasible to get trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) monomer. If a source of that last one that sells to individuals could be found it might just work.